Herring Scrap 40: Thesis the Days of My Life

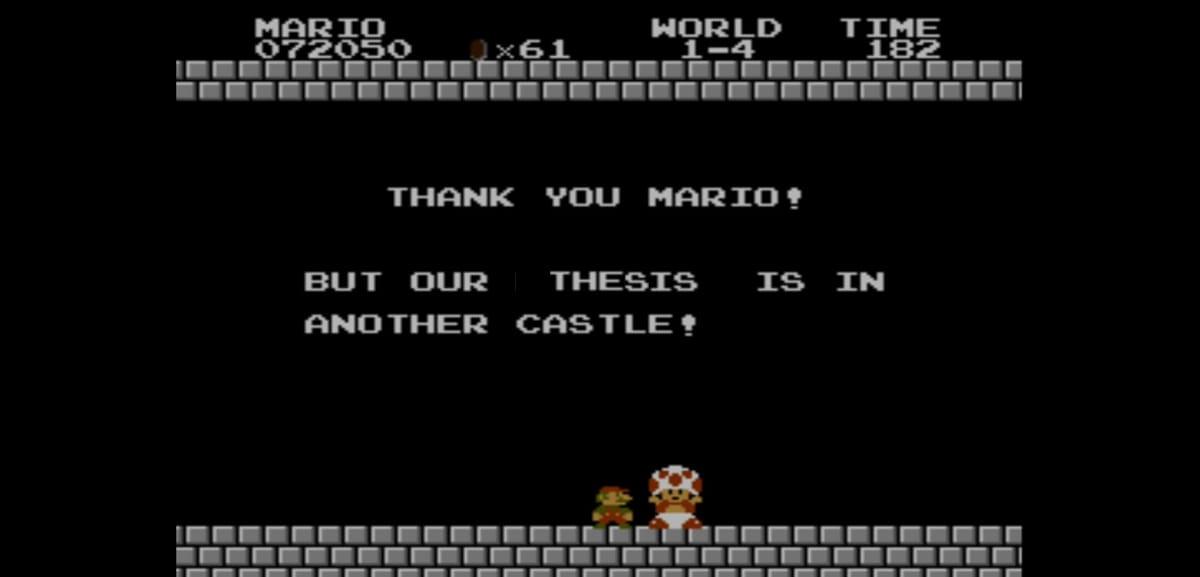

Progress on the thesis was steady and good this summer, and now I'm stranded in the uncanny valley that lies between the first complete draft and the final draft. It clocks in at 120 pages and some of the sections are a bit raw yet, but the thing exists and is right there, and I almost like it.

Hi! It's been a while. I can feel that scrappy twitch flaring up again, and so I thought I'd write, give an update about what I was up to over the summer and where that leaves me now, and foretell scraps which may follow.

My big project over the summer was to finish up my thesis at last. This is the thesis-in-progress that I mentioned way back in Scrap 16 and haven't really talked about since, though herring scraps has certainly been my favored forum for exploring many of the ideas that live in the thesis. Progress on the thesis was steady and good this summer, and now I'm stranded in the uncanny valley that lies between the first complete draft and the final draft. It clocks in at 120 pages and some of the sections are a bit raw yet, but the thing exists and is right there, and I almost like it.

A little while ago, partway through revisions on my current draft, I wrote a summary of the thesis:

In the course of several years living in Sitka, Alaska, I noticed and became curious about the discrepancy at the heart of this thesis: In governing/managing the Sitka sound sac roe herring fishery, the Alaska Dept of Fish & Game is applying a knowledge system about herring that seems out of sync with the lived experiences and observations of locals generally and Indigenous elders specifically. I recognized in this problem an important example of how scientific authority can override community opposition to extractive projects. I returned to school to develop this thesis, in hopes of better understanding this particular knowledge controversy.

In the thesis, I attempt to draw on a deep reservoir of archival material - decades of annual reports, newspaper articles, and Board of Fisheries records - to trace how the bundle of knowledge involved in herring enumeration and biomass allocation has been constructed by the State over time, to describe how that knowledge has then been enacted in the world, including by promoting an expanding commercial fishery, and to reflect on what this case study means in the context of concepts like Shifting Baselines Syndrome.

My theoretical framework draws principally on Science and Technology studies. I think of my methodology as being aligned with sociology of translation/association as described by Bruno Latour. I draw heavily on the work of STS scholar Sheila Jasanoff as well. Jasanoff identifies four generic pathways through which knowledge and social order get mutually constituted in the production of technoscientific objects, such as the thresholds and baselines of a fishery - these are representations, discourses, institutions, and identities. She calls these four pathways the "instruments of co-production". Her co-production idiom provides an apt lens for thinking through how a fisheries justification knowledge bundle is formed, and my objectives and archival findings are mapped onto those instruments of co-production. In defining the objectives, methods, and archives for the thesis I sought out moments of perennial emergence of the instruments of co-production over the course of decades, assigning a section to each:

1. (Making Representations) Through a content analysis of historic annual reports from the ADF&G herring research program, I provide an index of change in the design of herring counting efforts

2. (Making Discourses) Through a discourse/sentiment analysis of historic post-season commentary from fisheries managers in the local newspaper, I identify a pattern of persistent managerial optimism about stock status, even in years that are now characterized by modeling as having had low populations.

3. (Making Institutions) Through a regulatory analysis of voting patterns on rulemaking proposals by different groups, I identify the degree to which the regulatory apparatus - determined through an ostensibly public process - has been defined by ADF&G's own proposals.

4. (Making Identities) Through a sort of citational analysis, I provide examples of how outside authorities affirm, reify, and re-articulate ADF&G's scientific authority. Through this approach, I attempt to examine how contested scientific authority gets achieved and maintained, and trace social and institutional processes through which contingent, evolving technical practices became stabilized as authoritative expertise on the population trajectory of a fishery.

A final analysis section (Making a baseline) describes how these co-production processes enabled the 2024 establishment of statistical population baselines by which low and high abundance states of herring in Sitka are defined - transforming methodological inconsistency and scientific uncertainty into policy instruments, and setting public expectations for herring abundance.

I call the thesis "a model fishery in bad relations".

A lot of what's in there will be familiar to herring scraps readers - most of the findings of the thesis have been previously explored in scrap form, to some degree or other. There's been a whole lot of iteration to get to where I've gotten, a lot of false starts and cut sections and abandoned experiments in approach. I came in wanting to write in some way about herring historiography and/or governance in Alaska, and I have indeed done that... but I could just as easily have taken a number of different approaches. Perhaps they would have worked better, perhaps they'd have worked worse. For now, they don't exist; there's just this one, nearing the finish line.

The title hasn't changed: it's still called a model fishery in bad relations. I mean for the title to convey a few meanings. The governance and monitoring of the herring population which spawns in Sitka Sound and the commercial fishery which targets them is considered in some quarters to represent rigorous scientific fisheries management, and thus regard it as a "model fishery"; it is also a model fishery in the sense that the herring population and commercial catch allocations are set and understood through the use of a statistical model. I argue that this model/model fishery is in bad relations in two distinct but related ways: first, the human relations surrounding this fisheries governance paradigm have long been controversial and troubling for many, including sovereign indigenous nations. This is well documented. I also refer to the statistical phenomenon in the data that I've noticed: that a close look at the data - and a differentiation of how it has been arrived at differently for different years - betrays bad relations between the original meaning of the data and the meaning being made from it today. The data set used for decision making in this fishery has a rotten foundation, and much continues to be built upon it. Taken together, the title inverts the virtuous scientific rationalism of herring governance in Sitka Sound: what that governance is a model of is a fishery in bad relations. Many of the world's fisheries are or have been governed in bad relations with terrible and untold consequences, and we must come to terms with how and why and find a better way.

It's not just the title; a lot hasn't changed since I first made moves to go back to school a few years ago. When I applied, I wrote to my then-future, now-former advisor about the problem that I was concerned with as I imagined developing a thesis: "My concern about the knowledge-holding practices around herring management emerged through the case study of Sitka Sound. There, a quite extraordinary amount - more, perhaps, than can be said of any other place - has been observed, studied, written, said, sung, and danced about herring and human interaction with them. There, herring are legendary. And there, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game account fails consilience with the rest."

It's that last idea - that there's something amiss with the ADF&G account, and that the way it is amiss is important - that is now jeopardizing my securing of a degree. It's a simple position that's well substantiated but not well documented, and I haven't moved on from it. Much to the apparent chagrin of my former advisor, my thesis is about how ADF&G's disagreeable account was formed and about the power of that account in the world.

After the last draft, my now-former advisor thought so little of it that she recommended I secure my degree by coursework or write a different thesis. This is an advisor who flatly refused to read this blog (and discouraged it as an apt setting for academic ideation), who insisted that I not use coursework as an opportunity to work on components of my thesis, who never once introduced me to another scholar, who sent me zero suggestions for grants or awards or opportunities to pursue, and who hasn't actually had an advisee successfully complete a masters level thesis since 2019 (in four tries). And so when my complete thesis draft - which featured sweeping changes in response to her notes on a prior draft - came back with destructive feedback, I noted that that was a category of feedback that I'd have to broadly dismiss, and asked to schedule a thesis defense anyway. This request prompted my advisor to quit the committee, which delays my defense date indefinitely, as one cannot defend without an advisor. Thus I'm on a leave of absence until I find an advisor that believes my work isn't too far off from being interesting and valid.

I've been told by my former advisor and by one prospective advisor that the Sitka herring case as I've described it is beyond the reasonable territory of a Masters of Arts in Geography, that to say and do the things I try to say and do in the thesis go beyond the disciplinary bounds and would require some training other than the training I have been given by my department, would require both me and my advisor, whoever they might be, to have specialties that we do not. To criticize fisheries science, I've been told, one must be in a Fisheries Science Program; to criticize a model, I've been told, one must be a modeler. And to secure one's degree in this particular program, one must attempt to do neither.

Needless to say, these are not the belittling limitations that I went back to school for.

It'll be ok; my commitment is first and foremost to writing something good and worthwhile, and if I don't extract a degree from this silly institution in the process, whatever. At this point I'm pretty convinced that think I've found a perfectly adequate way to describe something that I've noticed in the world and the way I've noticed it, and I happen to think that the way I noticed (by starting with the assumption that the clear collective voice of Tlingit elders represents the most accurate available historical context of herring abundance trends, and using that assumption as a basis for interrogating the historical record) the thing that I noticed (concrete and material problems with the way meaning is made from old data that has escaped the attention of others) is important and interesting enough that I should keep going. I think that the big problem is that I haven't described it all perfectly adequately yet. It's not so far away, I think, but I do wish to be done soon.

With this thesis I've been exercising a worry that as the years tick by, more and more environmental sense-making is being made from more and more environmental data that doesn't make sense, and thresholds and baselines and allowances and quotas and existential expectations are being set accordingly. As I float woozily in academic purgatory, I hope to scrap in that same vein.

I'd like to use herring scraps in the coming months in two main directions - first, to further develop some elements of the thesis that have been elusive for me or that I don't articulate well so far, and maybe even to share some of the things that are working; second, to work on articulating some of the broader patterns, problems, insights, questions, and histories that this herring-centered research process of mine has yielded over the last few years. In particular, I want to write more about novel and legacy pollution at sea & shore - things like oil spills, anoxic dumps, noises, and nukes. These are big categories of anthropogenic events that - like climate change and overfishing - could cause catastrophic outcomes among marine organisms, but - unlike climate change and overfishing - aren't typically blamed for or attributed to those outcomes. A major part of my extracurricular work in the last few years has been to try to think through this attributional gap in ocean harms, and I haven't shared much of that thinking yet with you.

Together, I hope those approaches can help me develop and describe some bigger picture ideas about why we must monitor, with skepticism, what's going on inside the ecological truth machines which power extraction and wealth-making, and perhaps also explain why I've been so fascinated and troubled by the narrative power of fish stats.

Thanks as ever for reading.